New rules for payment and e-money institutions

Over the past couple of months, the FCA has been consulting on whether to apply the Principles for Businesses, and some other Handbook rules, to payment and e-money institutions and registered account information service providers. This marks another step in the FCA’s journey towards greater supervision of the non-bank payment services sector.

New Payments Supervisory Department

In a previous blog post in June, I commented on the new payments supervisory department and how this has come about not just because the second Payment Services Directive (PSD2) places more responsibility on competent authorities but also because the FCA’s outlook on payments has changed: they now recognise that being able to make payments is fundamental to the financial services sector and to nearly everything we, as consumers, do day-to-day.

Applying the Handbook

Aligning the payment and e-money regulatory regimes with the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA) regime is a big step internally for the FCA. Back in 2007 – 2009, when implementing the first Payment Services Directive, the decision was made to implement through standalone Treasury Regulations because it was deemed too complicated to implement through FSMA and the Handbook. The reasoning went that because the Directive is maximum harmonisation, which means that national implementing legislation must not exceed or fall short of its provisions unless expressly permitted by the Directive, there would be too many parts of the Handbook that would have to be ‘switched off,’ as it were. Far simpler to do an ‘intelligent copy-out’ from the Directive into the Payment Services Regulations 2009.

The complication with this approach has been that, both within the FCA and beyond, there has been a low level of understanding of the payment services and e-money regimes, simply because they are presented so differently to the FSMA regime, and, as evidenced by this consultation paper, there is a view that poor conduct cannot be tackled as directly, effectively and consistently as desirable.

The problem to be fixed

It’s clear from the consultation paper that the main driver for these changes is that the FCA has wanted to fix problems with the way some firms have communicated with, or misled customers and hasn’t been able to within the confines of the existing legislation and rules. Three examples are given.

- Suggesting they offer better exchange rates than they do. Back in 2016, the FCA warned payment service providers about using currency converter tools on their websites that show the interbank rate without explaining that this is not the rate the customer would receive. A further warning in 2017 noted improvement on behalf of only some firms and the FCA’s determination to stop this poor conduct with regulatory action. They also highlighted that that they would be receiving powers (in the Payment Services Regulations 2017) to apply the Handbook’s financial promotions rules, which has led to where we are now.

- Stating there are no charges for the payment service. Customers have complained to the FCA about a number of payment service providers who have advertised their services as free and without making clear that there will be charges applied by another entity in the payment chain.

- Implying they offer bank accounts. Some non-bank payment service providers have stated, or suggested, they offer ‘bank’ accounts, which the FCA believes could lead consumers to think the funds in the account are covered by the deposit guarantee offered by the Financial Services Compensation Scheme.

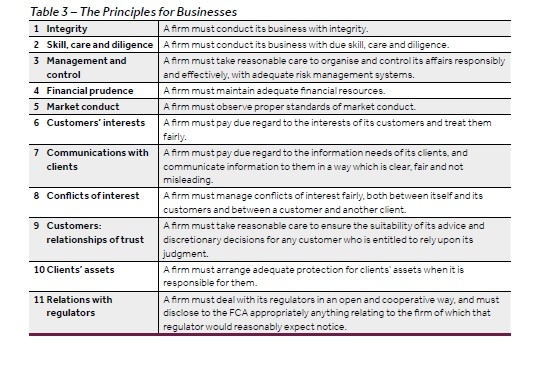

Offending firms should note that the FCA will not only fine but may also require restitution. Vanquis Bank Limited, for example, was fined almost £2 million earlier this year for breaching Principles 6 (treating customers fairly) and 7 (clear, fair and not misleading communication) and volunteered to pay just less than £157m to customers for not properly informing them of the cost of using their service.

Implementation

Aside from these miscommunication points, and a warning that account information service providers that make recommendations must be able to manage conflicts of interest and give suitable advice, the consultation paper is light on examples of the practical difference the application of the Principles will have.

This lack of guidance makes implementation more complex. A sector-wide one-off cost of £769,000 for ‘familiarisation’ was calculated based on the salary and overhead cost for the compliance and legal staff to read the changes and conduct a gap analysis though, interestingly, doesn’t include training for the wider business. But the FCA couldn’t estimate the one-off and ongoing cost of implementation. On the one hand, it is fair to say that since the Principles do not specifically require more than what is already included in the Regulations and various EBA guidelines there shouldn’t be significant implementation costs. On the other hand, the reason the FCA wants to apply the Principles is that they make it easier to fine firms for breaches, which points towards the need to be mindful of lessons learned in the wider financial services sector.

For firms with an embedded compliance culture this shouldn’t be onerous, but it will take time to consider the wider application of the Principles and demonstrate compliance. And these changes land amid a period of yet more change with open banking requirements due from March 2019 and strong customer authentication requirements in September 2019, not to mention the need to prepare for all possible Brexit scenarios. This proposal to not afford an implementation period – arguably the most materially impactful of the whole consultation document – is covered in a mere three lines of the 60 page document.

The consultation closes on 1 November so there is still time to put your view to the FCA, and I strongly recommend you argue for a longer lead-in time to allow for proper preparation.

If you would like any guidance on what the new rules will mean for you, please contact me or any of the fscom team.

This post contains a general summary of advice and is not a complete or definitive statement of the law. Specific advice should be obtained where appropriate.